Mary Randolph (1762-1828) was born into a notable Virginia family, with roots extending all the way to the union of Pocahontas and John Rolfe. Her father was a politician and her brother married the daughter of Thomas Jefferson. In the time-honoured tradition of notable families, Mary married her cousin, thus ensuring that she remained Mary Randolph after her nuptials too. The couple ran a plantation in Virginia at first, but then built a house in Richmond. Financial difficulties forced them to open a boarding house before finally moving in with one of their children. Throughout all, the Randolph dining room was considered an excellent place to spend time, and shortly before her death Mary Randolph decided to publish her knowledge in “The Virginia Housewife: or, Methodical Cook”. Her cooking may have been so popular because she advised her readers to only cook vegetables until they were crispy, rather than the usual advice of “boil your asparagus for 15 minutes”.

Method is what Mrs. Randolph was all about. In her preface and introduction, Randolph stresses the importance of precise recipes to allow the housewife to plan the cooking economically. The house should be run according to a regular system: “If the mistress of a family, will every morning examine minutely the different departments of her household, she must detect errors in their infant state, when they can be corrected with ease; but a few days’ growth gives them gigantic strenght: and disorder, with all her attendant evils, are introduced.” Rise early, Randolph advises, otherwise your whole day will be out of sorts – in “complete derangement.” I wish she wasn’t so correct on that point, dammit.

Randolph’s introduction to the book offers a fascinating insight into who actually did what in her household. While the servants have breakfast, the mistress of the house arranges the salt cellar, pickle jars, mustard and whatnot, because this way “they are in much better order than they would be if left to the servants.” The cook then cleans up, and the mistress goes in “to give her orders”. Everything intended for dinner is brought for the mistress to inspect and the ingredients are measured out and given to the cook. It’s important, Randolph adds, that the mistress supervises this: “we have no right to expect slaves or hired servants to be more attentive to our interests than we ourselves are.” Attention to detail will create a home where husbands are pleased, sons grow up moral, and daughters learn to run a house equally pleasing to their husbands in the future.

I think it’s fairly safe to say that Mary Randolph, and her intended audience, did not do any of the actual cooking. That would have been left to women like Mrs. Fisher. Randolph’s division of labour is clear – a diligent mistress of the house overseeing the untrustworthy slaves is the ideal situation.

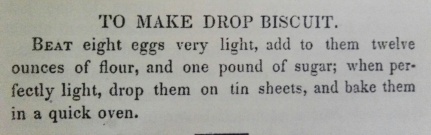

So what is Mrs. Randolph carefully instructing her cook to make today? Well, something rather simple – as simple a biscuit as you can imagine, actually, with only three ingredients. Drop biscuits are, I suppose, any biscuits where you can just drop your batter onto a tin sheet rather than cutting out shapes. Most recipes online have more ingredients, though – this recipe leaves out butter, any and all flavourings, and uses no leavening agent.

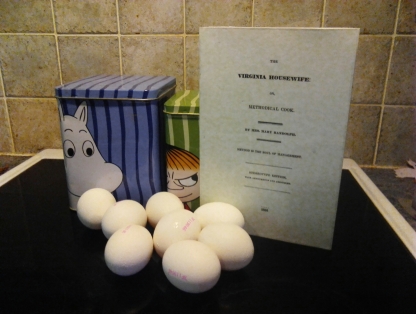

I make that 8 eggs, 450g flour and 340g sugar. I used plain white sugar.

What you need.

That’s a lot of eggs. Also, I hide my sugar in the green jar and flour in the blue one.

Beating eight eggs until they are very light takes a nice set of arm muscles, or, if you’re me, a handy-dandy electric whisk. I may be recreating old recipes, but there are limits to my dedication. Whisk your eggs however you wish, then add the other ingredients but stop whisking and stir instead. I ended up with a very runny batter, perfectly suitable for dropping. I interpreted “a quick oven” as “very hot”, so went with 225 degrees C. 8-10 minutes did the trick.

They may not be pretty, but I can always blame my slave cook for that.

What we have here is a quick and simple cookie, very plain in flavour but with an nice chewy texture. I can imagine these being a favourite with the kids on a plantation, something that the cook could stick in their hand and send them on their way. My kids certainly enjoyed them, although for my part I would add something to pep them up a bit. Lemon rind, perhaps, or cinnamon.

My two-year-old daughter found the cookies. She either didn’t like them but tried them all to be sure, or she liked them so much she decided to reserve them for herself, the only way she knew how.